Honoring Heroes on October 7th

Israeli Emissary Omer Karavani Shares a Story of Courage from ONE DAY IN OCTOBER

As we approach the commemoration of October 7th, it is essential to highlight the significance of the upcoming event organized by our Federation on October 27th. The program will commence with a 30-minute ceremony, followed by a tribute from our P2G community in the Western Galilee. I want to stress the profound importance of this event and to encourage maximum attendance. It will serve as a crucial moment of reflection and solidarity. (See the ads for more details).

Today, however, I would like to shift focus to a deeply moving book I recently encountered, which pays tribute to the heroes of October 7th—both fallen and surviving, soldiers and civilians alike. In moments of great danger, they made instantaneous decisions to perform acts of heroism and save lives.

To understand and realize the gravity of this tragedy, I thought it would be meaningful to share one of the stories from this collection. The book, titled One Day in October, features forty stories of forty individuals, each highlighting the courage displayed in the face of unspeakable adversity. This narrative reminds us of the profound impact of these events, which must never be taken lightly.

One chapter from the book tells the story of Police Superintendent Eyal Aharon. It is called:

“I’m Going to Save My Boys”

Written in Hebrew by Yair Agmon & Oriya Mevorach

Translated to English by Sara Daniel

CLICK HERE TO PURCHASE THE BOOK FROM KOREN PUBLISHERS.

(The story that follows is published with permission from Koren Publishers.)

When I was young, my father saw that when it came to religion, I wasn’t exactly following in his footsteps. He was a hazan, a cantor, my father. He spent all day in the synagogue, but I wasn’t into it, and my father said to me: “Listen. I have no problem with your decisions. In the end, it’s all between you and God. But I have one request to make of you: love your neighbor as yourself. Be yourself, and love people. That’s what I want from you.”

When I joined the police force, he told me the same thing. He said: “Listen, your decisions affect people’s lives. You can change someone’s life completely—for better or worse—and I ask that you judge everyone favorably. Be a mensch.” When I was twenty-five years old, he died on me. Far too soon. It shattered my world. But ever since, I feel him with me wherever I go. On October 7th, too, when there were so many miracles, so many things that didn’t make sense—people who looked on from the side said that it just didn’t make sense, they asked me if I was wearing some kind of magic cloak, some kind of invisible shield—I’m sure that it was him there with me. My father was the magic cloak I wore at the battle at Re’im.

On Shabbat morning I was at home in Kibbutz Beit Kama. An enjoyable Shabbat, good weather, everything’s good. My sons had gone to a nature festival a stone’s throw from the border. I have two boys: Shaked is twenty-three, Geva is twenty, and they’re both known for being party animals. This party was well organized, with all the proper permits from the police and the state, as it should have been. Until, in a second and a half, it turned into hell.

At seven in the morning, Geva calls my wife: “Mom, they stopped the party. The army called me up; pack me a bag for a week. I’m with Shaked; we’re on the way to Kibbutz Re’im.” This is what happened: they left the party, and when they reached the road, they could turn right or left. Whoever turned left to Be’eri died—almost all of them were killed—but my boys turned right. There’s a small bomb shelter by the entrance of Re’im, and they debated whether to go inside or not, and in the end, they decided to move on. Everyone who hid inside the shelter was killed. But they drove on into the kibbutz, where there was this one guy, Simhi, a hero, a real hero! He was walking around there saving people – even though he didn’t have a weapon—and Simhi said to them, “Come quick! There are terrorists!” and he ran with them to some safe room there. Later, I heard that he himself was killed.

As soon as she hung up, I got into uniform and drove off in the squad car, speeding like crazy. On the way, my son calls me, whispering: “Dad, there are terrorists in the kibbutz. Call the police; we ran into one of the houses, come save us!” I don’t wish a phone call like that on anyone; it was one of the most terrifying calls I ever got in my life. I hear him, step on the gas, and say, “Geva, don’t call any more—from now on, just message me. Not one call; I don’t want them to hear your voice. Hide.” That’s what I said to him on the phone, then the messages started coming.

The first message was, “They shot Shaked in the leg. Don’t come.” He told me not to come so that I wouldn’t put myself in danger. What happened was that my sons went into one of the houses with something like sixteen other people from the party. Geva and another soldier from an elite unit, Maglan, found a kitchen knife and a beer bottle and thought that they’d manage to fight off the terrorist. But then they realized that it wasn’t just one terrorist – there were dozens and dozens of them. So they went into the safe room, with everyone, and just seconds after they shut the door behind them, the terrorists start shooting in the house and throwing grenades. They’re in a safe room, sixteen kids from the party, including Shaked and Geva, and Geva and another guy take hold of the door handle and hold it shut. So, when the terrorist gets to the door, he tries to open it, but Geva’s a strong guy, and he holds it so tight that the terrorist can’t even move it—if he would have been able to move it, the terrorist would have realized that there was someone inside.

And then, out of frustration that he can’t open it, the terrorist just sticks the barrel of his gun right up to the door and shoots two Kalashnikov bullets—they’re armor-piercing bullets—and they go through the door and hit Shaked, my older son, in the leg. But Shaked doesn’t cry out; he doesn’t make a sound—he understood that he had to be quiet even though he was hit by two bullets, even though it feels like his leg is exploding, he realizes that he can’t make the slightest sound, or the terrorists will know they’re there.

The terrorists were sure there was some kind of problem with the door, that something’s caught, and they begin to go through the house. Meanwhile, Geva takes Shaked’s belt and makes him a tourniquet. And the terrorists come to the door from time to time and keep trying to open it, but they don’t succeed.

Me, from my perspective at this stage, I have no idea how big the thing was; I thought that there were three or four terrorists in the kibbutz, and that was it. I didn’t understand what was going on. On the way, I figured it made sense to drop off Geva’s bag at his base in Urim to make room for more people in the car, but when I got to the base there was no one at the security gate. Looking back, I had a miracle there, because when I was there—you can see it on the security cameras—when I was there, the terrorists were already inside the base murdering everyone who crossed their path. There was a massacre in the base while I stood there for a few minutes, waiting at the gate. I had no idea, and when I saw that no one was coming I turned around and left.

From there I drove to the police station in Ofakim. I had my revolver, but I wanted to get a rifle, and I figured that I’d ask another cop to come deal with the terrorists with me, no big deal. On the way, I see all these cars standing at the side of the road, but from my perspective they were just parked on the shoulder; I didn’t see any terrorists or bodies or anything. So, I go into Ofakim Station and see blood at the entrance. I see a cop with a head wound and ask him, “What happened?” and he says to me: “What’s the matter with you? Don’t you listen to the news? There are terrorists here in Ofakim, battles in Ofakim, in Urim, in Be’eri, and in Sderot.” Suddenly, the enormity of it hits me. We’d done police training for scenarios like that – terrorists infiltrating towns or taking over intersections to block reinforcements. At that moment, the sky seemed to turn black.

I said to the cops there, “Guys, I have children in Kibbutz Re’im; I’m going to go save them. Any chance someone’ll come with me?” and they said to me, “Sure, but let’s first see what’s happening here in Ofakim.” So, I said to someone there, “Fine, so give me a rifle,” and he says to me, “Sure, you can have a rifle, but there are no bullets; there are no bullets or cartridges left; the policemen who are fighting in Ofakim took everything we have. If you want, wait a little; the guy in charge of the equipment’s coming soon.” I said to him, “There’s no time to wait.”

Now I—the other cops think that I’m a little obsessive because I always keep a helmet and spare cartridges in my car. I’m prepared. They always said to me, “Why do you carry all that stuff around?”—Well, here you go. As I left Ofakim, I saw a police car on the way, Deputy Superintendent Davidov, the Rahat Station commander, a good friend, and he asked me, “What are you doing here?” I said to him, “I’m going to save my boys; they’re in Kibbutz Re’im,” and I saw from the look in his eyes that he couldn’t come with me. He has lots of trouble here, terrorists everywhere, so I said to him, “Go to your men. Good luck!” And I understood that that was it, I was on my own with this; no one else is going to help me. So, I set out alone for Kibbutz Re’im.

On the way, I see—it was terrible—I’m driving on the same route that I was on before, with all the cars at the side of the road, only this time I see them all from the front, and I see all the bodies, the blood, and I start to drive slowly, with a bullet in the barrel waiting for a terrorist to surprise me. It was like some horror movie, a totally apocalyptic sight. Some of the bodies were people who tried to run away, and some were burnt, and I’m driving between the corpses, and in the meantime the kids are corresponding with me, sending me pictures of Shaked’s wound, asking me when I’m coming.

PART 2 (CONTINUED FROM OUR COMMUNITY NEWSLETTER PRINT EDITION)

At about nine in the morning I get to Re’im, to the back entrance to the kibbutz, and at the intersection I see a cop motioning me to stay back, and the moment I see him, I realize that there are terrorists shooting at me from every direction, even before I braked, so I park the car on the side and open the door and start shooting back at their direction, without seeing them at all. And then they fire two RPGs at me, that’s a kind of anti-tank missile, and one missile hits just five meters away from me and explodes, and the other one hits about seven meters away, and I realize that if they shoot a third one then I’m a goner, so I lock the patrol car and sprint toward the kibbutz. And they shoot at me. Bullets go between my legs, over my head, I hear them whistle next to my ears, dirt flies up from the impact, but I just run. And as I run, I curse every cookie I’ve eaten lately– I mean, I’m fifty-three, not young, and not exactly thin, and I have to move forward as quickly as possible.

At the entrance to the kibbutz, I meet another four cops, and one of them says to me, “Do you have a cartridge to spare? I’m out of bullets,” and I say to him, “Here, take a cartridge.” I knew I was on my way to my boys, but I couldn’t say no to him. They had just evacuated a wounded cop, and they said to me, “Come, wait outside,” but I ran into the kibbutz. They didn’t understand why; they thought I’d gone nuts, but a few of the policemen came with me, they joined me. By the way, one of the cops that joined us – his whole backside was covered in blood, and I said to him, “You’re hurt! You’re dripping with blood!” but he said to me, “Yeah, I was hit by a grenade in Ofakim, but my legs can move, my eyes can see, and my finger can pull the trigger, so we keep going.”

So, we start making our way through the kibbutz, slowly, carefully, because there are terrorists around, and then I suddenly hear, “Don’t shoot! Police!” and I see a man in police uniform, light blue, with a police cap and insignia. He’s standing in front of me without a weapon, without anything. He’s smiling at me and says, “Take it easy, don’t shoot!” No accent or anything; he sounds completely Israeli. And my head begins working: where do I know him from, maybe from Ofakim, or from Arad, or from Rahat? As he approaches me, I say to him, “Don’t come any closer!” and his smile starts to fade, and I tense up, and I look at him, then he notices the four cops behind me who have reached me, and suddenly his smile completely disappears.

I ask him, “What station are you from,” and he answers, “Special Reconnaissance,” which doesn’t make sense because they have different uniforms, but I wasn’t quite sure because there were some cops who worked security at the Nova Festival. So, I ask him again, “What station are you from,” and he repeats the same answer, but by then I can see a green Hamas bandana peeking out from under his cap, then I spot more terrorists in camouflage in the shadows behind him, and I shout “Terrorist!” and I shoot. I hit him first, and then everybody joins me. Only later did I understand that this was actually an attempt to kidnap me.

Then a gunfight breaks out there at very close range, and once again, they have an RPG and machine guns, and we kill three terrorists there – some died and some ran away. The moment I understood that the gun battle was over, I continued moving forward into the kibbutz, making my way to the location that my boys sent me. I walk the whole time between bushes for cover. On the way I meet an old man who must have been eighty years old, a kibbutznik – only kibbutz types can speak like this – he says to me, “Hey, dummy, you just dumped three bodies on me here! What am I supposed to do with them?” So I say, “Don’t do anything with them! Run back fast into the safe room; there are a lot of terrorists here!”

On the way I also called my commander to update him about what’s happening, but while I was talking with him I heard someone shushing me from one of the houses. It was a young man holding a tiny baby – teeny tiny, about a month old – and the man says to me, “Don’t wake up my baby – either come in and be quiet or go away.” He was holding his hand over the baby’s mouth to keep him from crying – with one hand he held the baby and closed his mouth and with the other he held a gun. I just apologized and kept going.

When I was finally close, so close to where my boys were, I was creeping across the gravel when a small box suddenly flew out of the bushes. I looked at the box, the box looked at me, and boom, it explodes. I realized that it was an explosive charge, someone must have heard or seen me, and I started backing away. And then I stopped and waited for the terrorist to move, and when he moved, I shot him from a range of four meters. It all happened just a meter away from where my boys were.

It took me two and a half hours from the moment I got to the kibbutz until the moment that I got to the house, the safe room where they were. I make my way toward the house, get there, take cover, and carefully enter the house. My heart is pounding – and the house is empty. Just sand. Bullet shells. Blood. The safe room is empty. What a feeling that was. I was sure the terrorists had kidnapped them; I was sure that I had missed them. I sat myself onto the couch, laid my rifle on my lap, and buried my face in my hands. I said to myself, what do I do, what do I do now? That’s it. I’m in the lions’ den. I missed my moment, I failed, my mission had failed.

But after a few minutes there, suddenly I said to myself, Maybe I missed something, I’ll send them a message; maybe they ran away. So I send them a message, and they reply! They’re alive! I feel a rush of energy like I’m recharged – I see that the location was slightly off, that it had sent me next door! So, I stick my head out of the door and see ten terrorists, twenty, setting the house opposite this one on fire, trying to force the shelter door open. I send Geva a photo of that house. He sends back, “No, we’re in a different house,” and describes it, and I realize that they’re in a house right near where I am. Really close.

I make my way out, taking cover in the tall bushes, and wait for just the right moment to sneak inside without being seen. Then I see all the terrorists going into that very house; the house where the kids are. I see their commander come with a map, and he spreads the map out there under the pergola, and his terrorists go inside the house and come out to the pergola with cookies and coffee, and he gives them instructions; he talks and explains, talks and explains and I see his map is divided into command zones: you go here, and you go here, and I can see and hear everything because I’m barely two meters away. And I send a message to my son, “I’m right across from the house. There are twenty terrorists at the entrance. Stay quiet.” My son said to me that when he got that message, he almost had a heart attack.

Meanwhile, I sent a message to my station’s deputy commander, Tal Zarhin. I sent him my location, and I wrote to him that twenty terrorists are preparing for deployment here; send everyone you can. That’s what I wrote, and he understood the message. As I finished writing him, I suddenly heard a burst of gunfire right next to me. Some terrorist was probably shooting in the air for no reason, but my kids, who were inside and knew that I was outside, were sure that I was dead. That’s what my son told me, that when they heard the gunfire – they thought that their father was dead. That was it; the story’s over. So I went back into the empty house and took a selfie and sent it to them. I didn’t smile in the first photo, but then I took another one, and I smiled in that one.

I was sure that would be my last photo ever. I couldn’t see any way in my mind’s eye that I’d make it out of there alive. I saw how many terrorists there were; I heard the pickup trucks coming, and I realized that that was it – there was no army, no police; it was the end. I said to myself, I’ve smiled my whole life – I’ll smile in my last selfie, too.

I was there in the bushes for about an hour, until an IDF special forces unit arrived! They must have received my message with the location. I started to hear them coming closer, giving orders, “Turn right, cover from here, cover me from there.” The terrorists heard them coming too and started running away from the house. They left the pergola and ran off. When the soldiers reached me, I said to them, “Police!” and their commander, Colonel Roy Levy, patted me on the shoulder and says to me “What are you doing?” I said to him, “I’ve been here; I was the one who sent the location.” I warmed to him right away, that Roy. He’s no longer with us; he was killed in that battle.

Roy said to me, “Crouch down,” and I said to him, “I’m old, I can’t bend down, I have a tear in my meniscus. If I bend down, I can’t get back up.” He starts to laugh and says to me, “Forget it, just give me a situation report.” So I told him, “Listen, I’m here because of my sons. I’m trying to get them out of here; they’re in the last house on the right. I have to get them out. There are dozens of terrorists around, something like forty or fifty.” That’s what I said.

Roy says to me, “Got it. Listen carefully. You and I will go to the front of the house and distract the terrorists. I’ll send a team round the back to get your kids out.” So I said to him, “Okay, great. But there’s another house here with kids in the safe room, and they’ve set the house on fire, the kids could suffocate.” The path was clear because the terrorists had run away, so I ran with the guys to the other house, the one that was on fire, and we got the kids out of there. There were about fifteen youths, with soot on their faces, soot in their nostrils. They had breathed in so much smoke that they weren’t doing well. We brought them to a safe place, then the battle began.

The firing near me intensified, but it’s hard for me to lie down or kneel, so I took cover behind some tree and fired from there. The terrorists kept moving around and attacking from different places; it was major chaos, and they threw a lot of grenades. At a certain stage, I began moving forward, and as I moved the soldier beside me shouted, “You have a grenade on your foot!” I looked down and saw a grenade resting against my heel – but it didn’t explode.

At some point I started moving forward, and as I left my spot, I saw a terrorist maybe ten meters away from me. He came out of the bushes and positioned himself across from me and began to shoot; he must have shot six bullets, but none of them hit! He aimed right at me and shot and I just stood there, frozen, not moving, and he kept shooting. At some point his gun jammed, he lowered it, and as he lowered it three of us shot at him at once and he fell. And the officer there with me said to me, “Tell me, man, are you wearing a magical cloak or something?”

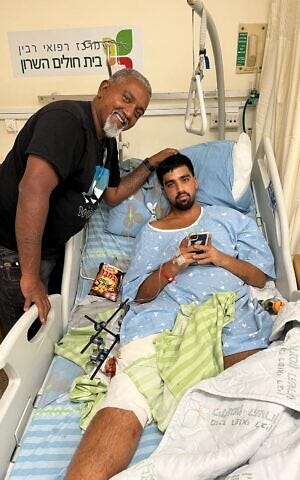

At that point the guys from the police special reconnaissance unit knocked on the window of the safe room where the kids were, and one of the policemen went in through the front door and brought all the kids out of there – fourteen youths came out, everyone but my kids, the guy from Maglan, and the medic who was with them. They brought Shaked out through the window. They couldn’t lift him up, so they put him onto a sheet and carried him out with the sheet. Meanwhile, more soldiers arrived, bringing a stretcher, and they transferred him from the sheet to the stretcher.

Just then, while they were arranging the stretcher, the terrorists who had spotted the rescue operation came and started shooting and throwing grenades again, and I remember that I saw Geva walking along carrying Shaked’s stretcher, and a grenade was thrown right next to them. Geva threw himself on Shaked and tried to protect him; he lay there on top of Shaked with his back to the grenade, and the grenade rolled right next to his head. If that grenade had exploded, they would have both been killed on the spot. But it was a dud, and it didn’t explode.

Roy Levy hadn’t forgotten about me, and he sent one of his officers to look for me – in the heat of battle, fighting for his soldiers, fighting for his life, he still thought about me. I went up to him, and he said to me, “Listen, your kids are at the infirmary, we rescued them, they’re safe and sound. We have the Negev Recon Unit here, we have the Masada Tactical Unit, and Sayeret Matkal commandos just arrived at the kibbutz – go to your children.”

On the way to the infirmary, on the way to the kids, I went into some house – I had to drink, it had been over five hours, so I went into some house. The house was wide open, a complete mess; there was no one there. I found a cup, filled it up with water, and took a sip. But it caught in my throat. I couldn’t drink, I couldn’t swallow. Here I was, in someone’s house, and the people who lived here might have been murdered; they might have been taken captive. I just couldn’t. I poured out the water, washed the cup, and moved on.

I was very lucky that day. God was watching over me. So many of my friends were killed before they even had the chance to fight. A good friend of mine was murdered in Ofakim before he had time to shoot a single bullet. He was murdered, and I’m still here. It’s simply Divine Providence; it’s all up to God – and my father sitting next to Him, persuading Him to let me live. He was a persuasive guy.

A month or so later I went to visit my father’s grave – I had to thank him. I truly believe that thanks to him, I’m still alive. I visited his grave, spoke with him there, then we went with the kids to synagogue and recited Birkat HaGomel, the gratitude blessing. From there I went to Jerusalem, to visit Roy Levy’s grave. I had to thank him as well. He didn’t forget me. I could have waited there on the battlefield for hours, and no one might have come, but in the midst of all the chaos, in the midst of the carnage, he remembered me.

When I met his wife and told her what happened and told her about our conversation and the jokes he made and how he remembered me in the heat of battle, she understood perfectly. She said, “Yes, that’s him; that’s exactly what he’s always like; that’s him.” I think it was good for her that I told her.

My friends are always asking me what motivated me, what kept me going, what saved me from losing hope even when everything seemed hopeless. And I want to say that today, whenever I see my boys – when I get back from work, when I eat lunch or dinner with them, when I see them, the answer’s clear – my children are still alive today.

I don’t know if this is optimistic or not, but ever since that day, at every funeral I’ve been to – and I’ve been to funerals – I imagine myself in the family’s place, standing at my own son’s funeral. I see the hostages’ families, I see their agony, and I think: Wow, I was nearly in that situation. That could have been me. The country is in a sad, sad place right now. No doubt about it.

On the other hand, I keep reminding myself that I should be the world’s happiest person. I was there, I made it out, I won; I won my boys’ lives, I won my own life back. It’s always with me, always, always – the thought that I was fortunate enough to succeed, to survive. So many others weren’t given that gift; they never came back. For me, that thought leads only to one place: a place of gratitude. I’m grateful for my life; I understand that my life and my sons’ lives are a gift. It’s a gift we cannot, must not, waste.